This is the second part of our 'Ultimate Guide to Writing a Memoir.'

To access the rest of the guide, click here.

So you've gathered everything you need to write your memoir - if you need some more help, make sure you've read Chapter 1: Organising Your Memories, where you can download our Memory Prompt Cheat Sheet to uncover forgotten memories. But what comes next?

There are many ways to structure your memoir. There is no right or wrong way to do it - but it’s one of the biggest choices you will make about your book. Structure is crucial to the readability of your book. You might write beautifully, but without any kind of structure, your words will be scattered and disorganised.

So how do you structure your life story? We’ve outlined five of the best approaches to help you choose.

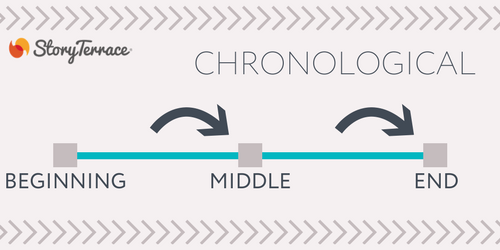

1. The chronological approach

One of the simplest ways to structure your life story and develop a narrative is chronologically - in the order that it happened. In this case, you’ll start at the beginning of your timeline and work your way through from birth to present day. Writing chronologically facilitates fluid and realistic character development, and as a result, allows events to mirror the way your book will be read.

A surprising example of a chronological structure: Time’s Arrow by Martin Amis

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1991, Martin Amis’ book is written in reverse chronological order. It follows the story of a doctor getting younger and younger as time passes in reverse. This disorienting narrative makes for an unsettling and irrational read and emphasises the importance of deliberate structure within a book.

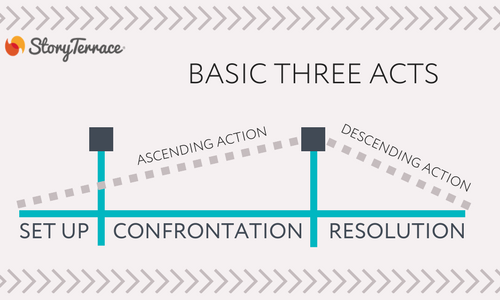

2. The Basic Three Act structure

The Basic Three Act structure splits the narrative into, unsurprisingly, three parts: the setup, confrontation and resolution. It is one of the easiest ways to structure your life story.

The setup introduces the characters, their relationships, and the environment they live in. It also presents a strong hook - an exciting incident that provokes a change in the protagonist's routine.

The second act - the confrontation - makes up the main bulk of your story. The stakes are raised throughout the act, until a major twist, usually a moment of crisis, initiates the start of act three - the resolution.

The resolution presents the final showdown and draws together and explains all the different strands of the plot.

If your timeline can be split into three clear sections along the lines of these themes, then this could be the structure for you. Often, a 'Three Act' book will be written chronologically, but it doesn’t have to be...

A great example of the Basic Three Act structure: The Titanic by James Cameron

The setup introduces Rose, an unhappy woman engaged to a man she detests. Jack rescues her, following her attempt to commit suicide. The confrontation sees the stakes raised when Rose’s fiance begins to suspect their affair. In a moment of crisis, the famously unsinkable ship hits an iceberg. The resolution follows Rose and Jack as they try to escape the sinking Titanic, ultimately ending in Jack’s death and Rose’s survival. Rose recounts the series of events as an old woman as the story ends.

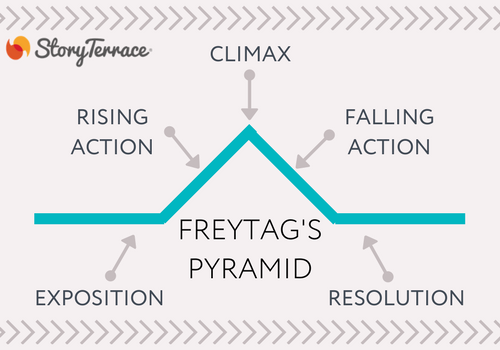

3. Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid is a more complex version of the Basic Three Act structure, with five parts rather than three. These are: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution.

The exposition, similarly to the Basic Three Acts’ setup, introduces the characters and backdrop of the story.

The rising action follows the series of events that occur straight after the exposition and leads up to the climax.

The climax is the turning point that changes the protagonist’s fate.

The falling action is the consequence of the climax, where the conflict between protagonist and antagonist unravels in a final moment of suspense.

The resolution is the same as in the Basic Three Acts, creating a sense of catharsis in conclusion to the story.

Compartmentalise the events from your timeline into these sections and you can start writing from any of the five starting points.

A great example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Little Red Riding Hood by Charles Perrault

The exposition introduces Little Red Riding Hood as she takes a basket of food to her grandmother’s house. Before she gets there, the wolf eats and takes on the identity of her grandmother. This is the rising action. The wolf convinces Little Red that he is her grandmother, and eats her in the climax. In the falling action, the wolf falls asleep. The huntsman finds the wolf and cuts open his stomach. The resolution sees Little Red and her grandmother freed, and the wolf killed.

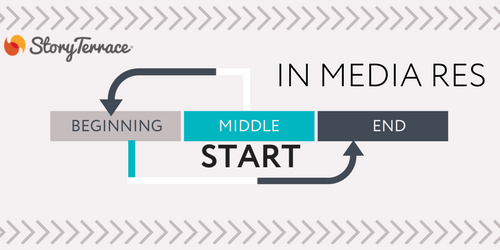

4. In Media Res

Latin for 'into the middle of things', it’s unsurprising that this structure starts your book right in the middle of the story. This is usually in the midst of a crisis, or at a crucial point of action. This structure gives the reader a sense of what’s to come before reverting to the beginning of the story to find out how they got there. It’s also a great way to hook the reader from the first page.

If there’s a specific event in your life that was a turning point, shaping who you are today, this might be an interesting place for you to start.

A great example of in media res: The Odyssey by Homer

The famous poem opens in media res, with most of Odysseus’ journey already finished. Flashbacks and storytelling describe the events and characters met along the way.

5. The Hero’s Journey

One of the most popular methods used to structure your life story is the Hero's Journey. It was first conceptualised by Joseph Campbell in his book, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, and has since been adapted by Hollywood executive, Christopher Vogler. There are 12 stages to the Hero's Journey.

The ordinary world introduces the hero, closely followed by the call to adventure - a challenge or problem. The hero, probably scared of dangers ahead, is reluctant to accept the adventure in the refusal of the call. Meeting a mentor gives the hero confidence to cross the threshold, committing wholeheartedly to the adventure of the special world.

The hero faces tests, allies, and enemies as they draw closer to the “elixir” in the approach to the innermost cave. The ordeal sees the hero pushed to their limits in pursuit of reward, before the road back. Consequently, in the resurrection, the now-changed hero returns with the elixir, commonly knowledge, back to the ordinary world.

.png?width=500&name=The%20Hero's%20Journey%20(2).png)

A great example of the Hero’s Journey structure: Star Wars directed by George Lucas

In the ordinary world, Luke Skywalker lives on moisture farm on Tatooine. R2:D2 gives Luke a message from Princess Leia, asking Obi-Wan Kenobi to help her as the call to adventure. Obi-Wan gives Luke his father's lightsaber, but at first, Luke is reluctant to accept his offer in the refusal to call. In addition, Obi-Wan, the mentor, offers to train Luke to become a Jedi (this actually happens before the refusal to call in Star Wars). Crossing the first threshold, Luke finally agrees to go with Obi-Wan to Alderaan to deliver the plans for the Death Star to Leia's father.

Han Solo and Chewbacca, their allies, agree to take Luke and Obi-Wan to Alderaan. In the approach to the innermost cave, the Death Star destroys Alderaan. They invade the Death Star and rescue Princess Leia, but Darth Vader kills Obi-Wan Kenobi in the ordeal. The reward sees Luke join the Rebels to destroy the Death Star, who also refuses Han Solo's offer to leave. Luke chooses to help overcome the Galactic Empire in the road back.

Luke remembers Obi-Wan's advice and destroys the Death Star using the Force in the resurrection, and wins a medal, finally taking his first steps towards becoming a Jedi in the return with the elixir.

At the end of the day, your story can be as structurally unpredictable as life itself. It’s your life and your story. We hope these methods have opened your minds to the vast possibilities and different forms your life story can take. But remember, there’s no right or wrong way to structure your life story: it’s up to you.